I was happy to review the exhibition “Eine Frau ist eine Frau ist eine Frau…” (A woman is a woman is a woman…) at the Aargauer Kunsthaus for the Swiss online magazine Republik. The full article can be read here (in German) – and a short excerpt (in English) is below!

“It is because of these, and many other reasons, that the effort of revisitation proposed by “Eine Frau ist eine Frau ist eine Frau…” becomes necessary, mandatory, in the times we are living in. The parallels between the time of these women artists and ours, however, also become painfully clear—and the ways in which they have been erased and forgotten could very well be the way in which a contemporary generation of women artists will be also erased and forgotten, in the future. How to create mechanisms to make sure this doesn’t happen? And how to make sure these kinds of exhibitions are not just a celebratory one-off? These kinds of questions are instrumental in thinking more broadly about the impact and importance of an exhibition of this kind. Alongside the overall effort of celebration through exhibitions, institutions need to conduct a larger work of reflection on the ways they collect, promote and support women artists, or the mechanisms of erasure that have been a constant in the history of art will continue to be replicated. It would be desired, then, that the process of making such an exhibition can result in a change in institutional attitude, and a conscious effort to change the ways in which women artists integrate—or not—national collections, art history and artistic discourse.

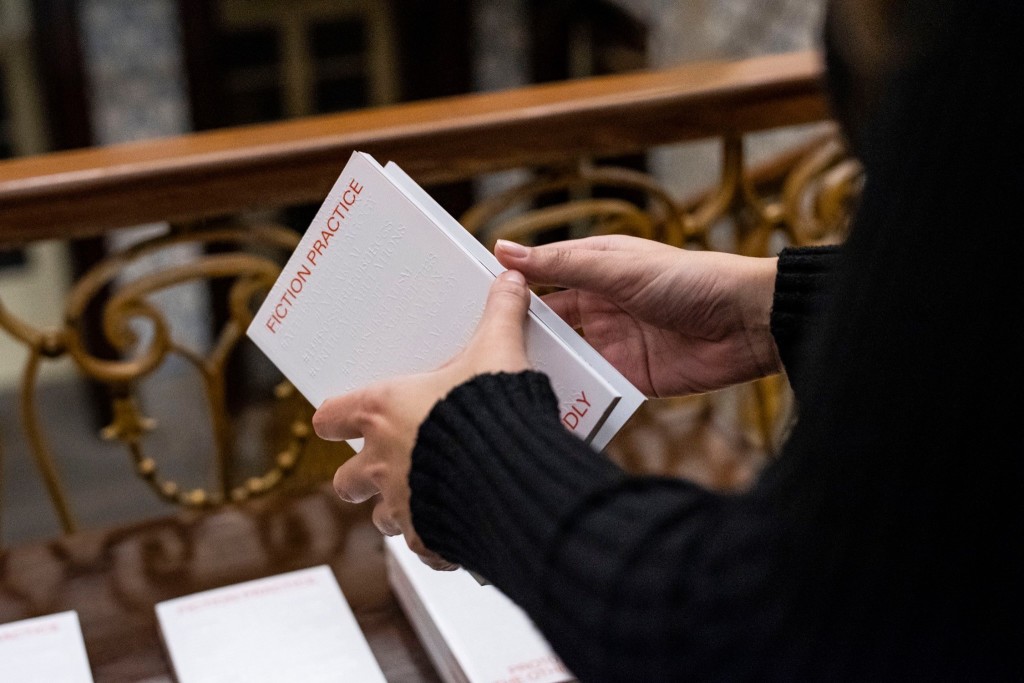

An important part of that effort also lies in the written word. After an exhibition, what remains? Beyond an institutional attitude, which can take months and years to manifest in a visible way, catalogs and written records can also make important contributions to writing a history that is invisible and forgotten. In this way, perhaps the most impactful legacy of “Eine Frau ist eine Frau ist eine Frau…” is the small brochure that serves as an exhibition catalog. Produced in a small format, and easily accessible for 5 CHF, the brochure is written as a compilation of biographies of all the women represented in the exhibition. The text is open in revealing what it knows and what it doesn’t know—for some of the artists, not much information was found in traditional sources. But by making itself available, this small glossary is the start of something bigger. It reveals a willingness to engage in scholarship that has not been done yet, and invites further contributions to such an effort. It is now a stepping stone, a marker and a starting point for all those who may be able to add to it, using it to revise, and to add, to a history of art that is direly incomplete.”